· Human activity damages more than 40% of seas

· First 'big picture' map worse than expected

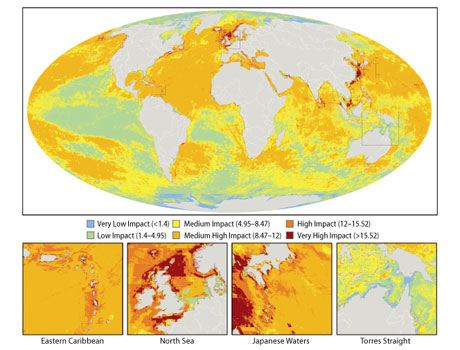

A global map of the overall impact that 17 different human activities are having on marine ecosystems. Insets show three of the most heavily impacted areas in the world, and one of the least impacted areas.

Fishing, climate change and pollution have left an indelible mark on virtually all of the world's oceans, according to a huge study that has mapped the total human impact on the seas for the first time. Scientists found that almost no areas have been left pristine and more than 40% of the world's oceans have been heavily affected.

"This project allows us to finally start to see the big picture of how humans are affecting the oceans," said Ben Halpern, assistant research scientist at the University of California, Santa Barbara, who led the research.

"Our results show that when these and other individual impacts are summed up the big picture looks much worse than I imagine most people expected. It was certainly a surprise to me."

Human impact is most severe in the North Sea, the South and East China Seas, the Caribbean, the Mediterranean, the Red Sea, the Gulf, the Bering Sea, along the eastern coast of North America and in much of the western Pacific.

The oceans at the poles are less affected but melting ice sheets will leave them vulnerable, researchers said.

The study found that almost half of the world's coral reefs have been heavily damaged. Other concerns rest with seagrass beds, mangrove forests, seamounts, rocky reefs and continental shelves. Soft-bottom ecosystems and open ocean fared best but even these were not pristine in most locations.

Previous studies of human impacts have focused on a single activity or on an isolated ecosystem, and rarely on a global scale.

Fiorenza Micheli, an associate professor of biology at Stanford University, said the maps should guide ocean management in future.

"By seeing where different activities occur and whether they occur in sensitive ecosystems we can design management strategies aimed at shifting activities away from the most sensitive areas."

To make the map scientists compiled global data on the impacts of 17 human activities including fishing, coastal development, fertiliser runoff and pollution from shipping traffic.

They divided the ocean into one-square-kilometre cells and worked out which human activities might have touched each particular cell. For each cell, the scientists allocated an impact score to look at the degree to which human activities affected 20 types of ecosystems.

Around 41% had medium high to very high impact scores. A small fraction, 0.5% but representing 2.2m square kilometres (850,000 square miles), were rated very highly affected.

Halpern said the results, which were published in the journal Science and presented yesterday to the American Association for the Advancement of Science annual meeting, still gave room for hope. "With targeted efforts to protect the chunks of the ocean that remain relatively pristine we have a good chance of preserving these areas in good condition."

Andrew Rosenberg, a professor of natural resources at the University of New Hampshire, who was not involved with the study, said: "Clearly we can no longer just focus on fishing or coastal wetland loss or pollution as if they are separate effects.

"These human impacts overlap in space and time, and in far too many cases the magnitude is frighteningly high."

He added: "The message for policy-makers seems clear to me: conservation action that cuts across the whole set of human impacts is needed now in many places around the globe."

Highlighting examples of action, the researchers said that, for example, fishing zones have been shown to help ecosystems survive better, and navigation routes across seas have been altered to protect sensitive ocean areas.

Although the research will be helpful, making conservation decisions will require more detailed research at the local level, said Micheli.

"Our results and approach, augmented with additional local information, can also inform management at a local and regional scale. Looking at the data globally, some information is lost."

Halpern said the map was a wake-up call. "Humans will always use the oceans for recreation, extraction of resources, and for commercial activity such as shipping. This is a good thing. Our goal, and really our necessity, is to do this in a sustainable way so that our oceans remain in a healthy state and continue to provide us with the resources we need and want."