The Australian prime minister, John Howard, has poured scorn on the idea of global warming. But now the trees are dying, the crops are failing and the rivers are drying up. As the country prepares to go to the polls, Julian Glover reports on the world's first climate change election.

The loggers are moving in on the Tamar valley. Photograph: Julian Glover

On an early summer's morning in northern Tasmania, the Tamar valley looks like an Australian slice of Tuscany. There are groves of walnut trees beside white-barked eucalyptus, a lavender farm, apricot orchards and small fields of olives. Vineyards run down to the river and fat black cattle graze the pasture. Yachts are anchored in the winding reaches of the tidal river. The Tamar seems a model of sustainable development - green and welcoming.

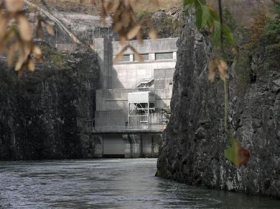

Except that the Australian government has just approved the building of one of the world's largest pulp mills in the middle of this scene. A 200-hectare (500-acre) polluting giant by the side of the Tamar river, the factory would accelerate - some say double - the already rapid pace of logging in the mountainous and verdant island state. Turned into woodchip and then exported as chlorine-bleached pulp, much of what remains of Tasmania's native forests may end up as cheap paper for the hungry markets of Asia.

This is not the first time that the island has found itself caught up in environmental conflict. The logging industry has long been a source of controversy as well as local jobs. The successful 1970s campaign to stop a dam being built on the wild Franklin river led to the birth of the world's first Green party. The Bell Bay pulp mill is now part of a much wider public debate over Australia's environmental future that is now shaping the country's politics.

Australia goes to the polls tomorrow in what is arguably a milestone in 21st-century history: the world's first climate-change election. It comes after a five-year drought that has seen some of the country's greatest rivers dry up and crops fail. A land that has grown rich over two centuries on the back of what seemed like unlimited space and resources - and which is booming through the shipping of coal and iron ore to fuel the furnace of China's economy - is confronting a far less comfortable reality of water shortages, failing crops and environmental collapse. But the logic of the new debate is emerging faster than the old politics can catch up. As the 21st-century wind changes, political faces are caught in 20th-century grimaces. There is a disconnect between national arguments and Saturday's election choices.

The story begins with Australia's conservative prime minister, the Liberal leader John Howard, the man who the polls say will be defeated tomorrow night - though Australians know there is a chance that the great survivor could pull off one last victory. His downfall, if it comes, will be symbolic for reasons that run well beyond climate change. An icon of global conservatism, he is the last of the Iraq warriors to seek re-election, after Tony Blair and George Bush. He stood alongside the United States in refusing to sign the 1997 Kyoto agreement. Howard poured scorn on the existence of climate change, though he has now been forced to change his mind. Australians can see for themselves that he was wrong.

"Salt is coming up out of the ground, trees are dying," says Geoffrey Cousins, a well-known Sydney businessman and former adviser to Howard who has now turned his efforts to stopping the pulp mill. "It is quite clear to anyone living in Sydney that rainfall patterns have changed, the pattern of storms is different. There has been a big shift in thinking and the mill became a concrete, readily understandable example of all of this, something we could actually do something about."

Facing Howard is the man who expects to become Australia's prime minister tomorrow night, the Labor party's leader, Kevin Rudd. A clever, bespectacled former bureaucrat from the tropical state of Queensland, he recently used his fluent Mandarin to chat to the Chinese premier Hu Jintao in front of the anglophile Howard - a humiliation that symbolised the way national priorities are shifting to Asia.

Yet Rudd has fought a highly restricted, personalised campaign, aping Howard more than opposing him on most issues. Friends - including Britain's former cabinet minister Alan Milburn - have turned Rudd into a brand: Kevin07. It is very reminiscent of New Labour. Rudd has fought on a handful of issues targeted at working families in suburban seats, especially the changes to employment law that were pushed through by Howard. Such caution has disappointed some supporters. Controversially, Rudd has also backed the construction of the Tasmanian mill - shaken by a Labor defeat in 2004, when the party promised to save the island's native forests in the last week of the campaign, only to be savaged on polling day.

But Rudd has been much bolder on climate change, making it a defining point of difference. He has promised to sign the Kyoto protocol as his first act of government - and the fact that the decade-old agreement is still a live issue in Australia is a sign of how far debate is behind Europe. For a car-addicted nation that was last week named as the world's biggest per-capita emitter of greenhouse gasses - Australians produce 27% more tonnes of carbon dioxide per head than Americans - it would be a significant moment.

"There is no doubt that over the past few years the impact of the drought has been to make voters personally experience what they see as a changing climate," says Lynton Crosby, the pollster and campaign strategist who helped Howard to win four elections in a row and directed the Conservative party campaign in Britain in 2005. "For the first time in 25 years in this country, the environment is an important voting issue." Crosby is no new-generation eco-rebel. That he can see the way the wind is blowing speaks volumes.

By the banks of the Tamar river in Tasmania, winegrower Peter Whish-Wilson has built up the Three Wishes vineyard and is also in no doubt that the climate is changing in politics as well as the skies. "We have had storms come through that we have never seen before," he says. "In the last five years we have broken every single temperature record - highest temperature, lowest, highest rain. Climate change is tangible; we can see it in the country. Farmers are coping with the worst droughts on record.

"The country is learning the hard way. It has always been seen as the lucky country, with a lot of land and resources, but you can't live in a lot of Australia now."

For him, the pulp mill is part of the choice facing Australia: between exploiting its natural resources or managing them. On the road that runs past his farm, huge logging trucks already pass every few minutes, loaded with wood cut from the hills. The scene confronting visitors to the forests is almost apocalyptic. Trees are bulldozed or blown apart with explosives and the ground cleared by fires, started by napalm dropped from helicopters. Any native wildlife that survives is culled by sodium fluoroacetate poison, allowing regimented new saplings to grow - monoculture on an industrial scale.

This, and the sense that the island is in thrall to the power of the giant timber business Gunns, is one reason Howard's Liberal party fears it will lose two key marginal seats in Tasmania tomorrow, on the back of Green party votes redistributed to Labor under Australia's preferential system.

Gunns, the company that wants to build the plant, argues that it will be "the world's greenest pulp mill". Opponents dispute that: they say that its chlorine processes are outdated and will pump dioxins into the fishing grounds of the Bass Strait. They also question the economics: the A$1.7bn (£720m) plant will require state funding and huge bank loans.

The logging company argues that "opponents of the development have resorted to misinformation, scaremongering and false claims". It has not been shy of taking on Tasmania's green movement, and in 2004 launched a multimillion-dollar claim for damages against a group of environmentalists. It is true that, as Gunns say, part of the Tamar valley is already industrialised. There is a metals plant at one end, and a woodchip mill, which will feed the pulp plant. But the planned site is untouched. "If it can happen here, it can happen anywhere. People have got to come to grips with the fact there has got to be a balance," says Whish-Wilson.

The journey from Tasmania to Sydney's eastern suburbs involves a dramatic switch of cultures. In the richest part of the country's largest city, Saabs and Range Rovers crowd narrow streets of Victorian terraced houses and huge glass and stone millionaires' palaces tumble down to the harbourside. There are boutiques and designer coffee bars, the haunt of Australia's pinot grigio classes, as well as Bondi beach and Australia's biggest gay community.

This is the Wentworth constituency of Malcolm Turnbull, the millionaire lawyer who took on the British establishment in the Spycatcher trial and went on to campaign, unsuccessfully, for a republic in a referendum opposed by most Liberals. By saving the monarchy, he said, Howard was "the prime minister who broke Australia's heart". At least until tomorrow, Turnbull is also the environment minister and one of the most striking players in Australian politics - a man of ability and undisguised ambition.

He could hope to replace Howard as Liberal party leader. Instead, Turnbull's political career may be cut short. As environment minister, Turnbull himself led the way in announcing a ban on the sale of tungsten light bulbs, a world first. But his seat ... solidly conservative for more than a century - is at risk after a backlash from voters who oppose the Tasmanian pulp mill. Lampposts across the constituency sport Green party slogans. The Greens expect a record vote in this election, but their vote is not concentrated enough to win seats in parliament. The irony is that if Turnbull is defeated, Labor, which also supports the mill, will win.

The scale of Green activism in Wentworth is one sign of a changing country. Another is the background of the man picked by Labor to fight the Sydney seat that sits next to Turnbull's. Elected as a Labor MP in 2004, and now - like Turnbull - his party's environment spokesman, Peter Garrett is the closest Australia gets to Bono. As the lead singer of Midnight Oil, a rock group that formed the soundtrack to rebellion for a generation of Australians, Garrett used his music to campaign for Aboriginal rights and environmental change.

Now he is accused of being a sell-out in a suit, kept out of the limelight during the election campaign by a party worried that he might frighten voters. In the ferocious TV attack ads allowed by Australian electoral law, he has been repeatedly described by the Howard campaign as one of Labor's "fanatics, extremists and learners" - after a supposed slip when he admitted that Labor's green policies appeared cautious but that "once we get in, we'll just change it all".

Garrett and Turnbull might deny it, but the two Sydney MPs have much in common. Both want to push further on the environment than their parties allow. Both probably privately wish the Tasmanian pulp mill plan would disappear. And both are tall poppies in a political culture that punishes individuality.

Westminster is a model of freethinking compared with Australia's House of Representatives and elected Senate. Rebellion against the party whip is not just frowned upon but banned: any MP who tries it risks expulsion. The result is a form of processed politics that encourages caution and blandness. David Cameron's attempt to modernise the Tories produces puzzled looks from Australian Liberals, still a party of white men sweating slightly in heavy suits and loud striped ties.

Howard himself will soon leave office whether he wins or loses - and he may lose in the most dramatic form possible, since his marginal Sydney seat of Bennelong will swing to Labor if the polls are right. Even if he survives, he faces a fate familiar to Tony Blair. Having long fended off the prime ministerial ambitions of his treasurer Peter Costello, he has been forced by a cabinet revolt to promise to stand down after the election. But Costello is an unconvincing performer with the droopy looks of a fall guy in a New York cop show and a political agenda almost as antique as Howard's.

According to Crosby, "the government is campaigning on the risk associated with change to an inexperienced team". It is a tactic Gordon Brown will surely use in Britain next time - and it might work. But it has allowed the Rudd campaign to set the terms of the debate. The Howard government has proposed an aggressive plan to intervene in Aboriginal affairs. Though it was much-discussed before the campaign, Labor has not challenged its fundamentals. Nor has Australia's presence in Iraq, or the future of the monarchy, caught national attention.

Politicians blame Australia's media culture for the decline in debate, but the fault lies with parties too. They have reduced campaigning to the mechanistic manipulation of numbers - seeking to catch the attention of the sort of disengaged and easily scared wavering voters who do not turn out in Britain but must do so by law in Australia or risk a $20 fine. That leads to turnout of more than 90%, but also crude tactics such as Howard's scare stories over asylum seekers in past elections, and a Liberal leaflet discovered this week that claimed to be from a Muslim group backing suicide bombers and thanking Labor from its support. Howard distanced himself from it quickly.

Labor has also indulged in attention-grabbing: Rudd exposed himself to an interview in which he was asked whether he would win a bar fight against Howard, and who he "might turn gay for". "My wife," he replied - which led the host to ask, not unreasonably, if she was therefore a man.

That demeaning of debate is common to many modern democracies: caught on camera seemingly eating his own earwax, Rudd faced mockery. The British tabloids would surely do the same to Cameron or Brown. Underneath all this there is a serious election trying to escape: it's about a society that is more prosperous than ever, but uncomfortable about the effect of prosperity on the way people live and on the planet's ecosystem.

"The Howard government has degenerated and is purely obsessed with its own re-election," says Lindsay Tanner, the Labor MP for inner-city Melbourne, a seat where the Green party is also strong. He is hopeful that the necessary superficialities of a campaign will not prevent the election of a government that can respond to environmental and social change. "We have been disciplined and focused and kept political attention on critical issues, with climate change and Workchoices employment legislation as the most obvious priorities," he says.

Back in Tasmania, Gunns claim that its timber industry will be part of this sustainable future. If elected, Labor will have to decide if it agrees. It will not have much time to think. Logging of new sections of native forest is set to start on Monday. Work on the pulp mill will begin within weeks.