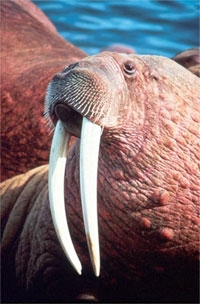

One of the most controversial voices in the global warming debate believes too much emphasis is put on extinction fears for ecology's poster animals

The global warming sceptic Bjorn Lomborg, has sparked fresh debate about the dangers of increasing temperatures with new claims that polar bears are not on the brink of collapse and are more threatened by hunting than by climate change.

In a new book called Cool It, Lomborg says many of the predicted effects of climate change - from melting icecaps to drought and flood - are 'vastly exaggerated and emotional claims that are simply not founded in data'.

Based on this 'hype', international leaders are spending too much time and money trying to cut carbon dioxide and the other greenhouse gas emissions blamed for global warming, rather than spending cash on policies that would help humans and the environment more effectively - such as stopping the hunting of polar bears, he argues.

'This does not mean that global warming will not happen, or that it will not predominantly have negative impacts,' writes Lomborg. 'But it is important to get the facts right: exaggeration will not help us select the right priorities.'

His book comes at a highly charged time for the climate change debate. Last week a British High Court judge, Mr Justice Barton, ruled that Al Gore's Oscar-winning film An Inconvenient Truth was guilty of 'alarmism and exaggeration' in making several claims about the impacts of climate change, including the plight of polar bears.

Claims in the film that the animals were drowning because they were being forced to swim greater distances due to disappearing ice were unfounded, the judge said. There was only evidence that four polar bears had drowned and that was due to storms.

The judge did go on to say there was good support for the four main hypotheses of Gore's film: that climate change is mainly caused by human-created emissions, that global temperatures are rising and are likely to continue to rise, that unchecked climate change will cause serious damage, and that governments and individuals could reduce its impact. On Friday, Gore was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his environmental work.

Lomborg's analysis has in turn been attacked by international polar bear experts saying that he has used out-of-date statistics to make his case and play down the plight of the world's biggest carnivores.

Lomborg made his name with an earlier book The Skeptical Environmentalist, which claimed fears about man-made climate change were overstated, and followed this up with Global Crises, Global Solutions, in which economists assessed the best ways of spending $50bn to improve people's lives, and put tackling global warming low on the list. Environment groups were outraged, but Time magazine listed him in the 100 most influential people in the world.

In his latest book Lomborg turns to the impacts of climate change, and says the story of the polar bears 'encapsulates the problems with many of the other scares - once you take a look at the supporting data the narrative falls apart'.

He claims that in this case many fears about polar bears being driven to extinction as global warming melts the ice floes they depend on to hunt and wean their cubs can be traced back to research published in 2001 by the Polar Bear Specialist Group of the World Conservation Union, the IUCN. It looked at 20 populations of polar bears in the Arctic, a total of about 25,000 bears.

That report, says Lomborg, found only two bear populations that were in decline, and two were showing an increase in numbers. It said the declining populations were in areas where temperatures were getting colder, and the flourishing populations in areas where temperatures were rising.

Other research referred to in the book shows that since the Sixties global polar bear numbers have increased from 5,000, says Lomborg.

More specifically, he challenges frequently repeated claims that the population of polar bears on the western coast of Canada's Hudson Bay fell from 1,200 in 1987 to 950 in 2004. The research actually goes back to 1981, when there were only 500 bears in that area, since when, he says, numbers have 'soared'. And, based on these figures, Lomborg calculates that legal hunting of 49 bears a year accounts for most of the recent decline in Hudson Bay, rather than climate change.

Finally, Lomborg says even though it is 'likely disappearing ice will make it harder for polar bears to continue their traditional foraging patterns', many can turn to the lifestyles of brown bears, 'from which they are evolved'.

'They [polar bears] may eventually decline, though dramatic declines seem unlikely,' he concludes.

He tries to explode other 'myths' too: it is too soon to say that Greenland's ice is melting fast and the threats of catastrophic sea level rise, extreme weather, drought and flooding have all been over-hyped, he says.

Last night Lomborg was accused of the same misuse of statistics which he levels at other scientists, environmental groups and the media.

Dr Andrew Derocher, chairman of the IUCN Polar Bear Specialist Group, said Lomborg's book was based on outdated statistics because the group had published an updated report in 2006, which showed that of 19 populations five were declining, five were stable and two were increasing; and for the remaining six there was not enough data to judge.

Derocher said data from before the Eighties was considered 'very questionable', that hunting was considered a 'minor concern in some populations', and that the decision by the IUCN to classify polar bears as 'vulnerable' was based on the unanimous advice of his committee of 20 members from the five 'polar bear nations' in the Arctic, including the only previous dissenter, a scientist quoted by Lomborg in his book.

Derocher, a professor in biological sciences at the University of Alberta in Canada, also criticised the idea that polar bears can adapt to the sort of life lived by the brown bear because they need to eat vast numbers of seals, which are also threatened by the changing ice. 'The changes of sea ice are evident to local people living in the north,' he said. 'Over the last 25 years that I've worked in the Arctic the changes are astounding. Polar bears are adaptable, but there are limits to this.'

Derocher said the author had not tried to contact him: 'Lomborg choosing not to ask for accurate information or using outdated information reflects a lack of scholarship.'

Speaking to The Observer, Lomborg said he concentrated on the 2001 report because it was so influential in promoting polar bears as an icon of climate change, but added: 'I would have liked to have known there was a new one.'

However, he said the latest research did not detract from his key argument: that the best way to protect polar bears was not to reduce greenhouse gas emissions but to cut or ban hunting. This is recently estimated to account for between 300 and 1,000 deaths annually. 'Shouldn't we stop shooting at least 300 polar bears a year before we spend trillions of dollars trying to save one polar bear a year through the Kyoto protocol?' he said.

Lomborg argues that international efforts to reduce greenhouse gases are too slow and expensive to solve the problems that climate change will bring. Instead money should be spent protecting threatened communities, tackling other threats, and investing in zero-carbon technology to reduce long-term emissions, he said.

'We constantly believe the only answer to any question is cut carbon emissions; very often it's one of the least efficient solutions,' he told The Observer

This is less controversial. But for many scientists it is not a question of either reducing greenhouse gases or adapting to climate change, but doing both, said Asher Minns of the UK's Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research at the University of East Anglia. 'The idea of adaptation to climate change is very old and there's as much work around adaptation as there is around mitigating greenhouse gases and coming up with low carbon technologies.'

· 'Cool It: The Skeptical Environmentalist's Guide to Global Warming' is published by Cyan-Marshall Cavendish, £19.99